Making tea with integrity: Building a company we can be proud of – An interview with Toshimi Nishi of Nishi Tea Factory in Kirishima, Kagoshima (2nd half)

2024.11.01 Tea CraftsmenINTERVIEW

- Matcha

- Ten-cha

- Kagoshima

As we drove toward our destination, the mountain roads running through northern Kagoshima Prefecture’s Kirishima City were covered in a dense mist. This region, which is home to the Kirishima mountain range that shares a border with Miyazaki Prefecture, has a foggy climate and extreme temperature differences that make it ideal for growing tea. In fact, the region is known as one of the leading tea-producing areas in the entire country.

Our car cut through the thick, mountain fog, causing our destination to come into view. Our objective this time was to pay a visit to Nishi Tea Factory in Kirishima City. This particular factory is known as the “oyabun” (boss) of the tea growing region, with its focus on producing flavorful and high-quality teas on a commercial scale while also using 100% organic cultivation methods.

The use of the term “oyabun” is also a reference to the unique personality of the company’s representative director, Toshimi Nishi. You get a sense of that somewhat bossy nature through his portrayals in various media and anecdotes. Additionally, Eiji Nakamura of Baisa Nakamura and Genki Takahashi of TEA FACTORY GEN—both of whom have appeared in CHAGOCORO before—used to work here, and we learned a great deal about Mr. Nishi’s personality from them as well.

When I mention this to Mr. Nishi as he greets me, he replies with a smile,

“Well, I don’t feel like I’m doing anything that seems bossy (laughs). I simply asked the farmers around me to work together, or asked if they could help me in some way. As a result of that, my circle of connections grew, and people simply started referring to me as ‘oyabun,’ and the name has kind of stuck.”

Upon arrival, we are treated to a cup of matcha in his office.

Nishi Tea Factory is especially famous for its organically grown tencha, which is the raw material used to make matcha before it is ground into powdered form. Typically, tencha is covered with a light-blocking cover before harvesting in order to help the tea leaves develop, ensuring that they are rich in amino acids. However, placing the tea plants in the shade also causes them stress, which weakens them over time. Furthermore, the “constraints” that result from the use of organic cultivation methods mean that the tea plants are unable to get sufficient nutrients. As a result, conventional wisdom in the tea industry states that organically grown matcha is lesser quality and also difficult to harvest, which make it unsuitable for producing tea on a larger scale.

Although, how does that relate to the tea that we were drinking here? It is a cup that features an amazing balance of sweet and savory flavors, with just the right amount of richness. I found it surprising that such flavor could be obtained using organic farming methods, so I naturally wanted to know how they are able to grow such tea.

After enjoying our cup of matcha and taking a short rest, we are taken on a tour of the production site.

Nishi Tea Factory features production lines for sencha, gyokuro, black tea, and also matcha (tencha). We were shown two different tencha factories as part of our tour. The oldest was built in 2005, while the newest began operations in 2020.

First, we set out for the older factory. Once inside, I was surprised to learn that the first thing Nishi Tea Factory does is “wash” the tea leaves. This is one of the key points that truly sets Nishi Tea Factory apart from the competition.

“Basically, it is considered a sin to wash the tea leaves. It’s not generally accepted in our industry. However, simply washing the leaves can remove more than 60% of the various substances and living organisms that may have attached to the leaves over time, including heavy metals, pesticides, environmental hormones, and also insects. Since tea is a plant that is grown outdoors, it is important to eliminate any uncertain elements that might have attached themselves to it. It would be quite problematic if any foreign objects or harmful ingredients were to be found on the plants later on. We want our tea to be safe and for our customers to have peace of mind when they drink it, so we feel it’s best to wash the tea leaves first. Therefore, we wash our tea leaves so as to improve their quality. As a result of that, however, we have to focus on producing tea that doesn’t experience a drop in quality even after it is washed.”

Indeed, I had never heard of tea producers washing their tea leaves before. Since Kagoshima Prefecture features volcanically active regions such as Sakurajima, many factories utilize machines to wash their tea leaves, but Mr. Nishi chooses to use this equipment not to combat the introduction of volcanic ash to his crop, but to improve its quality. It is a well-known fact that tea leaves that have been picked should not get wet, but Nishi Tea Factory’s relentless pursuit of safely producing tea has led to a method that essentially does away with that axiom. Right from the very start, I was impressed by Mr. Nishi’s attention to detail, but he goes even further in his attempts to create tea that is both safe and delicious.

“We rarely use things like bucket conveyors when moving the tea leaves within the factory. Using such equipment can cause residue from the tea leaves to slowly build up over time, which can then become a breeding ground for bacteria. Instead, we use a ‘blower’ that essentially relies on the power of wind to transport the tea leaves through the line, which can make it harder for bacteria to grow.”

I find it amazing that they pay attention to even minor details such as how the tea leaves are transported throughout the factory. That would not be the end of my amazement either. For many customers, it can be quite difficult to even imagine what kind of journey the tea leaves must experience in order to go from the fields to the “tea” that they drink on a daily basis. We all want the tea that we drink to be safe and delicious, but upon hearing Mr. Nishi talk about all of the detailed improvements his factory makes to ensure those goals are met, you really get the feeling that he is “making tea that is truly good for people.”

While still in a sense of awe regarding Nishi Tea Factory’s adherence to cleanliness, which could best be described as their “aesthetic,” we were even more surprised by the attention to detail they showed to the various other processes that followed the washing of the leaves.

Next, we were shown a place that featured two long and thin tower-like nets.

“This is a tea leaf spreader. Once the tea leaves are washed and then steamed, they’re sent to this machine and allowed to float in the wind. When you smash tea leaves, they will fold in along the middle vein and then break. This property is utilized during the sencha production process. You know how sencha consists of thin curls? Tencha is different. As the leaves are folded, moisture builds up in there, so when you apply heat later on, that particular portion begins to steam and then turns red. So for tencha, you want the leaves to remain unrolled, so that they can dry evenly. That’s why we have this netting, which allows the leaves to float in there without colliding into each other. Our older machine didn’t work all that well for such purposes, so I contacted the manufacturer and set about making various improvements to it myself.”

Passing through the tea leaf spreader completely removes the accumulated moisture from the leaves, which are then transferred to the roasting process. Next up, we are shown a large brick kiln.

“There are four-tiered lanes within the roaster, so the tea leaves that emerge from the tea leaf spreader are transported upward while they are exposed to heat. The bottom tier is the hottest, with the tea leaves being roasted with far-infrared rays at temperatures of up to 200 degrees Celsius as they make a sizzling sound like that of roasting rice crackers. As the leaves are carried upwards, the temperature of the kiln drops as they get further from the heat source. Essentially, the leaves are first roasted and then dried. Normally, tea is roasted only after it has been dried, but in the case of tencha, it is important that it be roasted first. Although the leaves are technically roasted, it is really just the edges of the leaves. This process is what gives matcha its unique flavor. If the leaves aren’t roasted at this point in the process, the end product will not taste like matcha. It will smell somewhat off. That’s what makes this process so important.”

Naturally, this particular method was not simply devised overnight. Mr. Nishi constantly sought ways to produce his tea more efficiently through the process of trial and error, until eventually arriving at the methods he utilizes today. Furthermore, even though he finished making the improvements to his kiln last year, the company continues to search for other areas in need of improvement or further enhancements that can be made to existing processes.

Moving on, we were shown around a third factory that was located nearby. Unlike the first factory we saw, which featured a meticulous attention to detail while retaining the charms of an older building with its handcrafted kiln made of brick, this factory was built in 2020 and it shows, with a very modern look and feel.

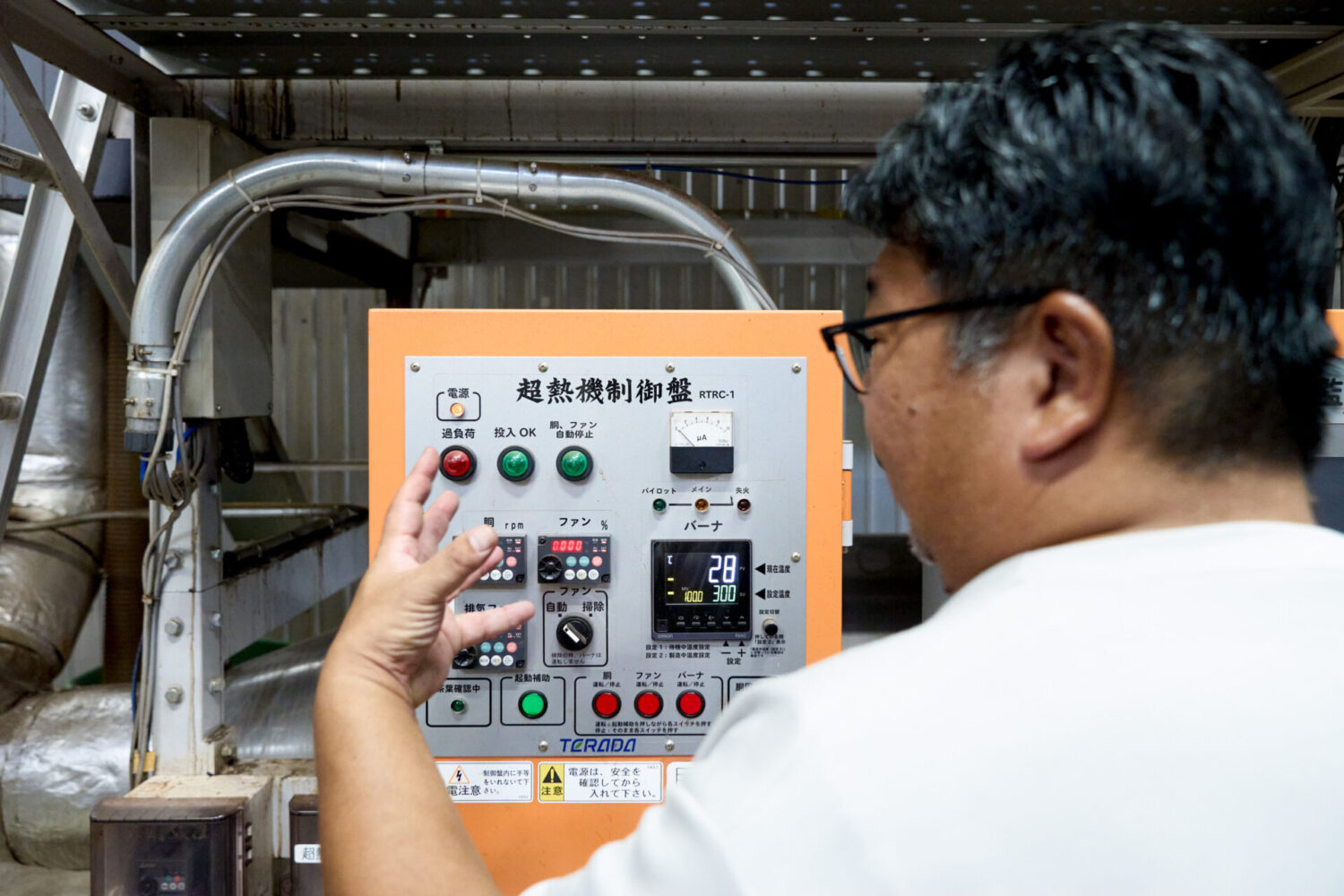

The monitoring room located near the central entrance includes a system that uses machines to check for clogs along the line and also to control the temperature. This factory also includes various examples of state-of-the-art machinery.

“Basically, I ended up proposing various improvements and other initiatives for each of the machines. For example, the machine we use to dry our tencha was inspired by the dryers used in China for making pan-fried tea. It emits hot air that reaches 450 degrees Celsius, so I figured it’d make a good tencha kiln. I gave it a try and it turned out to be a good choice for our needs. Previously, the usual method for drying tencha was to use a machine called a net dryer, so our clients were quite surprised when we presented our idea to them. The older machines and methods are fine when there’s a logical reason for using them, but you’ll never evolve if you just follow tradition without even thinking about the reasons why.”

I was also quite surprised to learn that most of the factory’s machinery had arisen from Mr. Nishi’s suggestions. Take, for example, the refrigerated container that is used to store the fresh leaves. This is actually quite rare for such storage solutions in Japan, and naturally, also came about after collaborating with a research institute. Inside, the fresh tea leaves are stored at a temperature of approximately 10 degrees Celsius so that they remain fresh for as long as possible.

Similarly, the tea leaf washing machine also features improvements that were made by Mr. Nishi. Previously, the machine’s filter would get clogged with dirt while circulating the water that cleaned the leaves, but he redesigned the system so that it removes the dirt while the water is circulating. In fact, this system has become the de facto standard within the industry.

If Mr. Nishi is lacking what he needs, he’ll simply make it himself.

While it is easy to say such things, you can imagine just how much trial and error went into creating the final product once you see it.

Given my initial image of Mr. Nishi as an “oyabun,” I had figured him to be a rather broadminded individual open to pretty much anything, but during our interview, I came to feel that he was the exact opposite. As we toured the factory, I felt like he was more of a realist who rigorously develops his theories and then puts them into practice in order to create the perfect tea.

How did Mr. Nishi develop this level of tenacity? As I was pondering that question in my head, he said something that immediately gave me somewhat of an answer.

“We have dealt directly with wholesalers since the days of my grandfather, without visiting the market. As a result, I feel like I’ve witnessed both the rise and fall of our industry. I think that experience gave me the ability to quickly recognize and adapt to the trends and needs that our industry faces. I take those insights and try to decide what kind of tea we should produce in the future. Therefore, I do not fear change. I feel like many farmers are essentially artists at heart, but that can often lead to a rather self-centric way of thinking. Naturally, we have similar aspects to our own personalities, but I feel like we are also constantly thinking of ways to respond to the industry’s never-ending changes. In that respect, I think it gives us something of an edge over the other tea factories out there,” says Mr. Nishi.

The list of surprises for me did not end with the factory tour. In the second part of this interview, we’ll take a look at Nishi Tea Factory’s tea fields. The level of thought and effort put into them was much more than we could have ever imagined. Mr. Nishi also shares his thoughts regarding his late father, who served as the previous company president.

Toshimi Nishi

Born in 1975, he is the third generation owner of Nishi Tea Factory in Kirishima, Kagoshima Prefecture. The company was originally founded in 1954 by Mr. Nishi’s grandfather, Hiroshi Nishi, as a leaf purchasing business. Later on, his father, Yoshimi Nishi, opened his own tea farm and the company has continued to expand ever since. In 2000, the company received official Japan Agricultural Standards certification as an organic tea farm. It also built a tencha processing factory in 2005. In 2010, Toshimi Nishi was appointed as representative director.

Nishi Tea Factory

798 Manzen, Makizono-cho, Kirishima-shi, Kagoshima

nishicha.com

Photo by Eisuke Asaoka

Text (originally in Japanese) by Rihei Hiraki

Edit by Yoshiki Tatezaki

Coordination by Nanami Kanai

2024.05.24 Teaware ArtistsINTERVIEW

2024.10.04 CHAGOCORO TALKINTERVIEW

2021.07.13

2021.07.16

2021.11.23

内容:フルセット(グラス3種、急須、茶漉し)

タイプ:茶器

内容:スリーブ×1種(素材 ポリエステル 100%)

タイプ:カスタムツール